He and my beloved sister are the two beings to whom my intellect is most indebted. William Wordsworth, 25 June 1832

|

Three people, one soul

About the soul relationship between the Wordsworths and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

In August 1803 William and Dorothy Wordsworth embarked on a six-week tour to Scotland. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, by that time a close friend of six years, accompanied them for the first two weeks. Lately, however, the friendship had shown cracks. Coleridge's opium addiction - and subsequent capricious behaviour - had strained the relationship. The joint trip was intended to strengthen their ties again, and support Coleridge's withdrawal. The trip would provide a change of air for a few weeks. The intention was good, but soon stranded on foul weather, Coleridge's depression and William's bad mood. On the fifteenth day, just past Loch Lomond, the latter suggested that Coleridge should return home. And so their ways parted. Dorothy wrote in her travel journal:

It rained heavily this morning, and, having heard so much of the long rains since we came into Scotland, as well as before, we had no hope that it would be over in less than three weeks at the least, so poor Coleridge, being very unwell, determined to send his clothes to Edinburgh and make the best of his way thither, being afraid to face much wet weather in an open carriage.

Recollections of a Tour in Scotland, August 29

That mutual friction was at the root of the company's breakup is evident from a note Coleridge made in his diary just after they had parted ways: 'Would that I had never met them!' Neither did he walk straight to Edinburgh, but made a wide arc through the Scottish Highlands. For seventeen days, with no a map, he followed his nose and walked like a madman, covering 263 miles in eight days.

One soul

The friendship between the Wordsworths and Coleridge began when Coleridge made his first visit to the siblings in June 1797. The rapport was instant. According to tradition, Coleridge once described the relationship with the words 'We are three people, but only one soul'. This striking characterisation of their intimate companionship appears in many of their biographies. But in fact the sentence is a free adaptation of what Coleridge actually wrote: 'For though we were three persons, it was but one God'. The surviving version is not entirely correct, but it aptly illuminates the truth of the special bond between the two men and the woman - at least initially.

At their first meeting Coleridge immediately made a deep impression on Dorothy. She wrote to a friend:

You had a great loss in not seeing Coleridge. He is a wonderful man. His conversation teems with soul, mind, and spirit. Then he is so benevolent, so good tempered and cheerful, and – like William – interests himself so much about every little trifle. At first I thought him very plain, that is for about three minutes. He is pale and thin, has a wide mouth, thick lips, and not very good teeth, longish loose-growing half-curling rough black hair. But if you hear him speak for five minutes you think no more of them. His eye is large and full, not dark but gray; such an eye as would receive from a heavy soul the dullest expression, but it speaks every emotion of his animated mind. It is more of the ‘poet's eye in a fine frenzy rolling' than I ever witnessed. He has fine dark eyebrows, and an overhanging forehead.

The admiration was mutual. 'She is a woman indeed!' Coleridge told his publisher '- in mind, I mean, & heart – for her person is such, that if you expected to see a pretty woman, you would think her ordinary – if you expected to find an ordinary woman, you would think her pretty! – But her manners are simple, ardent, impressive.' And, he said, 'Her information [is] various – her eye watchful in minutest observation of nature'. They had an obvious click.

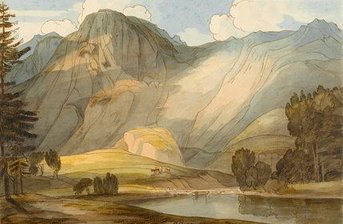

Quantock Hills

That first meeting between Coleridge and the Wordsworths took place in West Dorset. There Dorothy and William lived at Racedown Lodge, a mansion that a wealthy friend had made available to them. Coleridge, who had met William briefly twice before, was supposed to be staying there for several days. The sojourn lasted more than three weeks. The young poets read their works to each other daily and discovered great unanimity. At the end of those weeks, they couldn't say goodbye. Two days after their new friend left, the Wordsworths packed their belongings and moved some forty miles west to Alfoxden House, a rented country house less than an hour's walk from Coleridge's cottage in Nether Stowey, Somerset. There, in the Quantock Hills, the trio took countless long walks in the year to follow, by day and by night – by sun, rain and moon. Ideas flew back and forth on philosophy, literature and political developments of their time - the failed French revolution, the imminent invasion of England by France, the corn laws, the abolition of slavery. The conversations in the hills were a source of inspiration. Coleridge stated twenty years later that with pencil and notebook in hand he made studies like a painter, and moulded his thoughts into poems, while the subjects and images engulfed his senses.

At the time, Dorothy started writing a journal (The Alfoxden Journal) from which Coleridge and her brother drew inspiration and borrowed ideas and lines. Twice the two men tried to write a poem together. That failed, but the intensive collaboration resulted a year later in the publication of a joint collection of poems: Lyrical Ballads. English Romanticism was born.

Mad german poet

Lyrical Ballads was published in January 1798, anonymously, according to Coleridge, because 'Wordsworth's name is nothing – to a large number of persons my name stinks.' The latter comment referred to Coleridge's radical politics which had aggravated conservative circles.

Wordsworth contributed nineteen poems to Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge only four, but his included the longest among them: The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere (668 lines). The Rime also opened the collection. The critical reception was negative, especially of the long opening poem. According to the Analytical Review:

We are not pleased with it... In our opinion it has more of the extravagance of a mad german poet, than of the simplicity of our ancient ballad writers.

A friend of Coleridge's called the poem 'A Dutch attempt at German sublimity', i.e. a clumsy attempt to profess high literature.

Among the critics' concerns was the archaic spelling with which Coleridge wanted to give the ballad an authentic touch. He used 'Ne' for 'no', 'cauld' for 'cold', 'ancyent' for 'ancient' and 'marinere' for 'mariner'. Many readers found the story incomprehensible and incoherent. Most of Coleridge's contemporaries didn't know what to make of the work. But there were exceptions. Another of the poet's friends expressed his enthusiasm, albeit with a minor comment:

For me, I was never so affected with any human Tale. After first reading it, I was totally possessed with it for many days - I dislike all the miraculous part of it, but the feelings of the man under the operation of such scenery dragged me along like Tom Piper's magic whistle.

The pile keeps growing

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Coleridge modernised the spelling for the second edition) still enchants, despite the 'hocus pocus' it contains. The poem is certainly neither incoherent nor incomprehensible. That it is open to multiple interpretations is what makes it so interesting. After his death, in 1834, Coleridge fell into relative obscurity. Interest, however, revived in the early 20th century. Nowadays, there is an unending heap of books and articles about the poet and his Mariner. And the pile keeps growing. ►